Sherwood: The Living Legend

The term forest that we use today, did not necessarily mean an area of densely wooded land during the medieval period. Royal Forests usually included large segregated areas of wetland, heath or grassland, anywhere that was a safe refuge for the royal game, such as stags, harts and boars. In 1184, Henry I’s Assize of Woodstock was the first official act of legislation relating wholly to the Royal Forest. Forest offences would henceforth be punished not just by fines but by full justice as exacted by Henry I. No person shall have a bow, arrows or dogs within the Royal Forests. Dogs living near the forest had to be clipped, to prevent them from hunting. In each county with a Royal Forest there shall be chosen twelve knights to keep the venison and the vert. The twelfth chapter recommended the death penalty only for the third offence. There were two seasons for the royal hunting of the deer, November to February and June to September. But Summer was the best season when the deer was fat (or in grease).

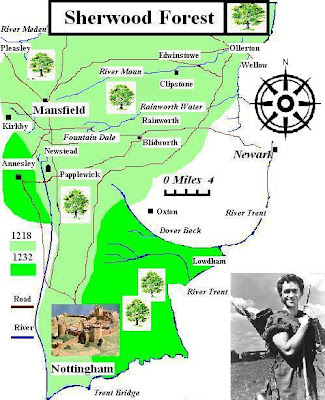

It was the chief forester who had the responsibility of preserving the laws of the royal forest and in the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries members of the distrusted and disliked Neville family held this post. The chief forester travelled the country holding forest eyres, or courts, in the different counties. From 1239 his job was divided and two justices were appointed, one for the forests north of the River Trent, one for those south. Sherwood’s forest courts during the early medieval period, were originally held at Mansfield where, between 1263-87 the average cases for trespass of venison were about eight a year. Illegal hunting was either quite small or, probably the efficiency of the foresters and verderers was poor!

At the king’s command, the chief forester protected the beasts of the forest, the red and fallow deer, the roe and wild boar. He earned a shilling a day and was permitted to have a bow bearer. Although the early Robin Hood ballads are deficient of any references to medieval forest law and its wardens, there does seem to be two allusions to this practice.

In stanza 9 of Robin Hood and the Monk, Robin Hood says:

But Litull John shall beyre my bow,

Til that me list* to drawe.

*that me list=it pleases me

And stanza 5 of Robin Hoode his Death:

And Litle John shall be my man,

And beare my benbow by my side.

Below the chief forester came the wardens, then the verderers. But maintenance of the forest and its game was the task of the ordinary, riding and walking foresters.

On Palm Sunday 1194, Richard I , whilst staying in Nottingham rode off into Sherwood Forest to enjoy two days at the royal hunting lodge at Clipstone.

On the 3rd March, Richard King of England set out to see Clipstone and the forest of Sherwood, which he had never seen before and it pleased him much and he returned to Nottingham.

John Manwood (?-1610) a gamekeeper, forest justice and writer during the reign of Elizabeth I, is said to have found, in a tower of Nottingham Castle, an aunciente recorde which he included in his Forest Laws in 1598:

In anno domini King Richard being a hunting in the forest of Sherwood did chase a hart out of the forest of Sherwood into Barnsdale, in Yorkshire, and because he could there recover him, he made proclamation at Tickill and diverse other places that no other person should kill, hurt or chase the said hart, but that he might safely return into the forest again, which hart was afterwards called a hart-royal proclaimed.

Clipstone became the principal royal hunting lodge in Sherwood Forest and was later known as King John’s Palace. It was probably built in 1160 and eventually spread over an area of at least two acres. In the first year of his reign, King John took up residence here and by the fourteenth century it had been extended to include a number of chambers, Kitchen, King’s Kitchen, Great Hall, Queen’s Hall, Great Chamber, Great Gateway, Long Stable etc. Part of it still stands today. During this time all the English kings hunted there, Henry II at least twice, Richard I once, John six times and Henry III made three visits. Between the reigns of the three Edwards, the royal hunting in Sherwood reached its peak. With five visits from Edward I, his son Edward II came six times and Edward III was the most frequent visitor with nine visits. But alas, no document survives of any of these kings meeting Robin Hood in the royal forest!

After Richard’s coronation, Prince John received Clipstone and Sherwood Forest, which was formerly part of the old estates of William Peveril. At the time of the Norman Conquest, Peveril had been granted extensive properties in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, including the High Peak and Sherwood Forest. But in 1155 the possessions of this family were forfeited to the crown and were administered on behalf of the monarch, by the High Sheriff of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire.

Between 1212 and 1217 the notorious Philip Marc, High Sheriff of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, had custody of Sherwood Forest. Marc came from Touraine, just south of Loire and together with Gerard De Athee, Brian De Lisle, Robert De Vieuxpont and others, became part of King John’s hated newly imported foreign agents. He was later condemned like others in Magna Carta, but was never removed from his position as High Sheriff of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire and Constable of Nottingham Castle. The protection racket passed down from Philip Marc and the successive Sheriff’s of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire was not stopped until 1265.

One of the well documented criminal bands that terrorised Nottinghamshire and hid out in Sherwood Forest from 1328-1332 were the Coterel gang. Their leader James Coterel was said to have recruited twenty members of his outlaw band from Sherwood Forest and the Peak District. It was said, he and his brothers rode armed, publicly and secretly, in manner of war, by day and night and committed acts of murder, rape and extortion. But la compagnie sauvage, as the gang members were referred to, also served in Edward III’s wars against the French and Scots and some even later served in the government!

In 1328 John, James and Nicholas Coterel with their gang, robbed Bakewell Church of ten shillings. Sixty inhabitants of Bakewell were accused of aiding and abetting them. Two years later it is recorded that Sir William Knyveton and John Matkynson were murdered by the Coterel brothers who, by that time had links with another equally murderous and violent outlaw band, the Folville brothers of Leicestershire.

Members of the Coterel brother’s gang included an Oxford don, bailiffs, chaplains, vicars a knight, a soldier, and a counterfeiter. An ally of this infamous band of outlaws, was none other than Sir Robert Ingram, High Sheriff of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire.

“In the forests,” wrote Richard Fitz Nigel (d.1198) treasurer of Henry II, “are the secret places of the kings and their great delight. To them they go for hunting, having put off their cares, so that they may enjoy a little quiet. There, away from the continuous business and incessant turmoil of the court, they can for a little time breathe in the grace of natural liberty, wherefore it is that those who commit offences, there lie under the royal displeasure alone.”

“In the forests,” wrote Richard Fitz Nigel (d.1198) treasurer of Henry II, “are the secret places of the kings and their great delight. To them they go for hunting, having put off their cares, so that they may enjoy a little quiet. There, away from the continuous business and incessant turmoil of the court, they can for a little time breathe in the grace of natural liberty, wherefore it is that those who commit offences, there lie under the royal displeasure alone.” When the Normans came to England, forest covered a third of the land, although gradual encroachment by the plough had already begun to take its toll. But the land did not have to be wooded to fall under Forest Law, many towns and villages were under jurisdiction and the whole of Essex at one time, was known as the ‘King’s Forest of Essex.’

The strict forest laws, ‘in order to keep the peace of the king’s venison,’ caused a great deal of hardship for those that lived in or near the Royal Forest. Dead wood could be taken from the forest for fuel, but no bough was to be chopped down. No timber or undergrowth could be used for shelter and it was forbidden to carry a bow and arrow. Dogs kept within the forest had to be ‘lawed,’ which was defined in ‘The Forest Charter’ of 1215 as the cutting of three talons from the front foot without the pad.

The wild beasts protected by law were the red deer, the roe, the fallow deer and the wild boar. A favourite few were sometimes given special hunting privileges, but it was forbidden, even for them, to touch the red and small fallow deer.

During the reign of Richard I, Sherwood Forest was held by Prince John, who granted it to Ralph Fitz Stephen and his wife Maud de Caux. They were given the special privilege to hunt hare, fox, cat and squirrel.

This cabalistic verse indicates the four evidences by which according to feudal laws a man was convicted, (like Will Stutely in the movie) of deer stealing.

Dog Straw (drawing after a deer with a hound)

Stable Stand (caught with a bent bow)

Back Berond (carrying away the venison on his shoulder)

Bloody Hand (hand stained with blood).

Edward the Confessors ‘Red Book’ has the following caution:

Ommis homo abstrest a venariis meis, super poenam vitae.

(Let every man refrain from my hunting grounds on pain of death).

Administration of the Royal Forests was the responsibility of the chief forester and his wardens. These men were never popular and in a late ballad, Robin Hood’s Progress to Nottingham, Robin as a youth manages to kill fifteen foresters.

Some lost legs, and some lost arms,

And some did lose their blood;

But Robin hee took up his noble bow,

And is gone to the merry green wood.

They carried these foresters into fair Nottingham,

As many there did know;

The dig’d them graven in the church-yard

And they buried them all on a row.

Here we have an example of how the discontent and oppression caused by the harsh, merciless foresters were repaid in the ballad makers world. This ballad is not dealing with an historical incident, but we can be certain that it was the vain dream of many a poor man.

The forest laws were very harsh during the start of Norman rule, but with their financial problems, both Richard I and John were prepared to sell off certain areas of Royal Forest to wealthy nobles. Landowners paid King Richard 200 marks to release a large area of Surrey from Royal Forest and similarly, King John received 5,000 marks from Devon.

Three clauses in Magna Carta were forced upon King John, to lighten certain Forest Laws and the young king, Henry III had to agree to the Forest Charter of 1217 exacted by his barons. This charter redefined more clearly the Forest Laws and disaforested certain areas. It also limited the number of meetings held by the forest courts, which had become an administrative burden for those living near the forest. Archbishops, bishops, earls and barons were now given the right to take one or two deer during a journey through the forest and punishment for stealing venison was reduced from death and mutilation to a heavy fine, imprisonment followed by banishment.

This charter was not of course a final settlement and records of forest inquests reveal a vivid picture of the discontented attitude of the people during the thirteenth century:

(Thirteen people)…... and others of their company whose names are to be found out, hunted with bows and arrows all day in Rockingham Forest (in 1255) and killed three deer. They cut off the head of a buck and put it on a stake in the middle of a certain clearing………….placing in the mouth of the aforesaid head a certain spindle, and they made the mouth gape towards the sun in great contempt of the lord king and his foresters.

© Clement of the Glen 2006-2007